“At the bottom of each and every living being’s heart dwells a call wrapped up in silence that needs a voice and words. There are beings who move speechless through life for, unuttered, this call gets hold of the truest, the more decisive words, the words that could change these beings’ fate. To be imprisoned by the word unsaid, by the muffled moan, by the stifled pleading, by the gift that returns to ourselves like a stone without being given, resembles a kind or slavery: the silence of that which is not asked and that which is not offered.”

(Los bienaventurados [The Blessed]- María Zambrano)

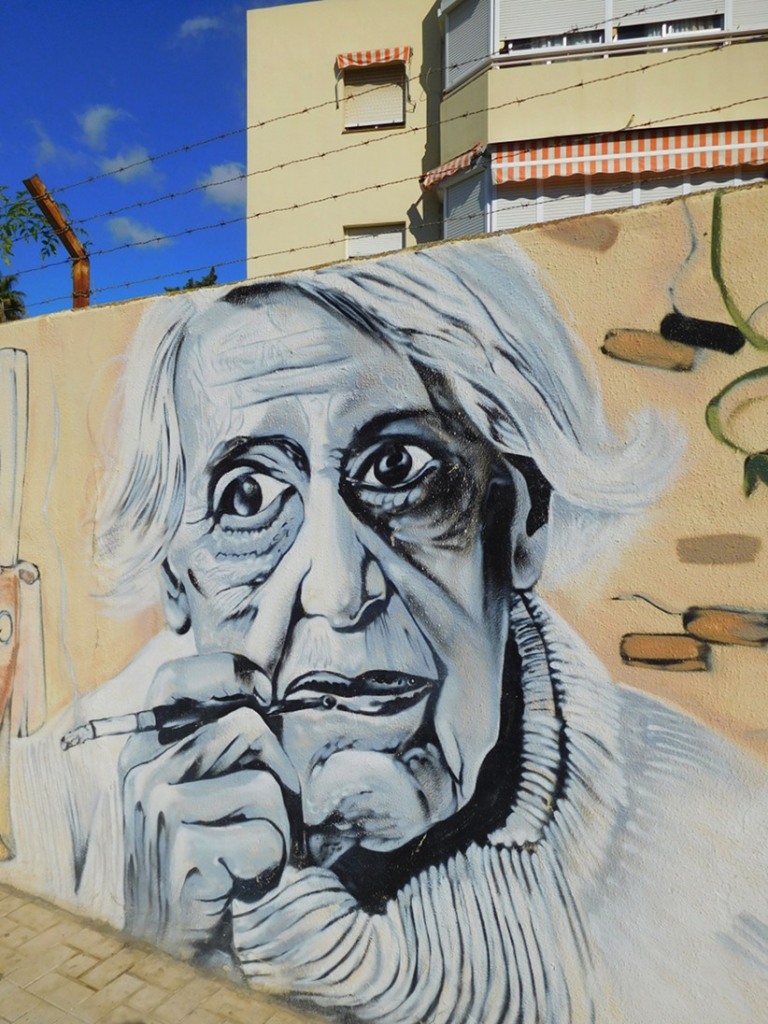

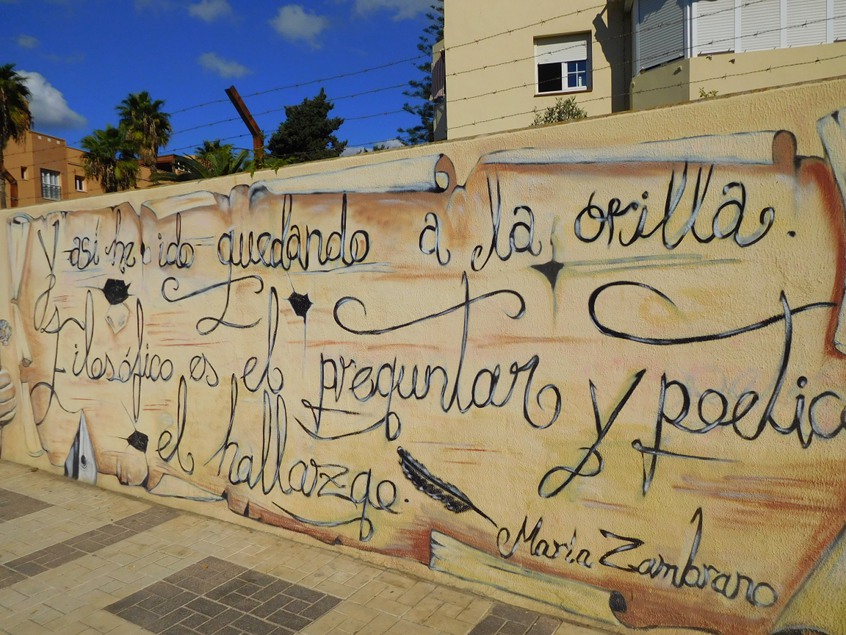

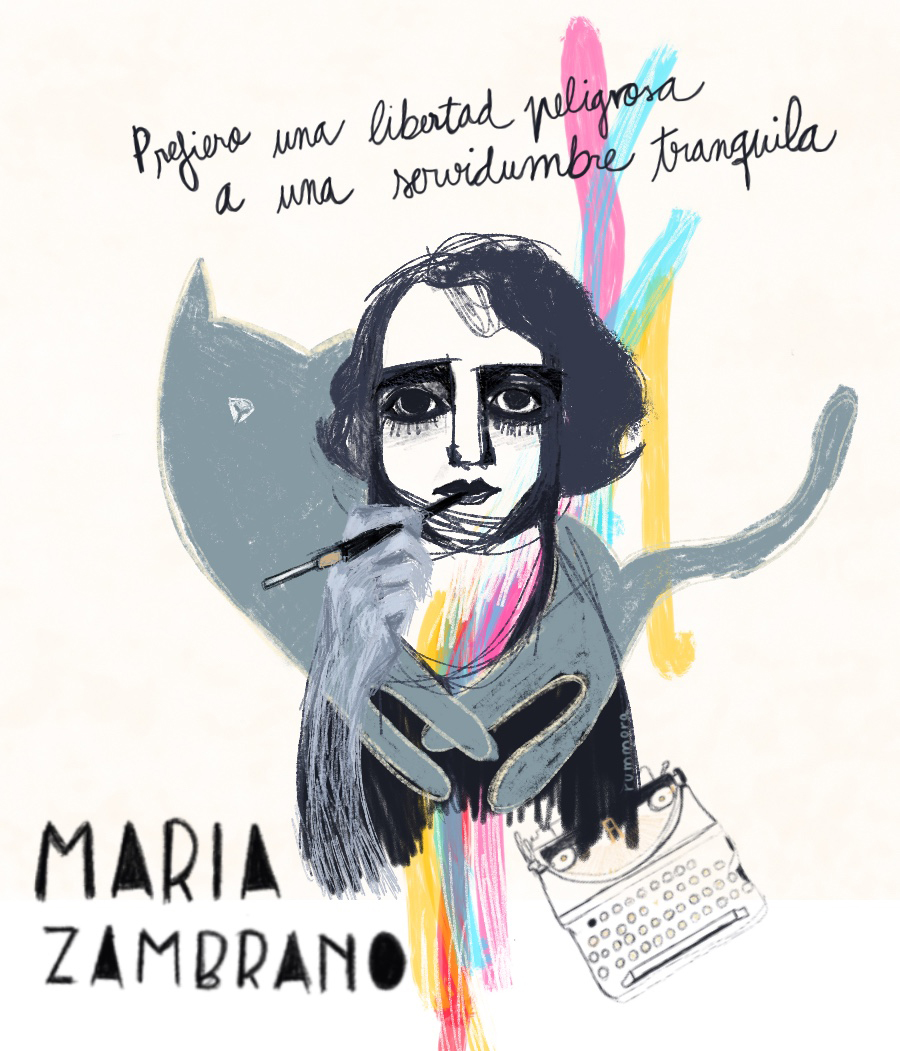

María Zambrano was a XXth. century Andalusian philosopher, whose life was marked by exile, a convalescent health and, most of all, an intense commitment to the word as a tool and key to ask questions and attempt answers about being, about the human and the divine. Given the poetic style of her philosophy, reading her may be no easy endeavor, but it is undoubtedly worthwhile. We can quickly grasp her relentless intention to always make the word stand out as “man’s primary element” (the same as air, fire, water and earth are), a fragment of meaning materialized in a rhythmic sonority, which connects or approaches, or at least tries to as much as possible, human inwardness and the context.

In one of the chapters of El hombre y lo divino [Man and the Divine] she states:

“(…) Because dialogue emerges in a specific silence encompassed by words born from a knowledge that does not wrap up in itself, from the knowledge that discovers itself in community; it is the silence that opens dialogue within itself, though for a very long time nobody may get to access that chamber. The word of dialogue can remain for a long time with no other answer but silence, thus gaining, sometimes, in depth…”.

After reading this paragraph, I immediately thought about a concept I always make an extra effort to get through to my pupils, especially those who are beginners or those who would like to improve their speaking skill: the irreplaceable importance of learning from the exchange with others; mainly training to listen, always attaching to each utterance a fraction of true, deliberate silence where the other person’s words can touch down to, later, be made our own (and I mean doing this in a literal, practical way, under every and any kind of circumstances, not just on philosophical grounds).

It would seem that what we, humans, find it hard to understand is that being open to the words of others, first and foremost, allows ourselves to open up: it leads us not only to an attitude of reception but also to an attitude of letting our selves go, of being able to say, of beginning to unbridle desire, independently of forms, of the formal aspect: we stop controlling the gates to our inwardness, eventually expanding our inner vessel. We make room for the other person’s words, we let them mix with ours, as two outflows meet and merge, whose combined tides will very probably manage to wear off, patiently and persistently, those elements in the context that might become an obstacle to the free flow of fluency.Also, it is also worth interspersing right here a question, reminding ourselves of a mystery: let’s imagine, what could have motivated human beings, back then in the remoteness of prehistoric times, to utter the first word ever? In the multiple possibilities of an answer to that question, We may find more than one matter worthy of reflection, even though we will never get to any certainty (certainty is a Western cultural feature, and almost an absolutist one; occasionally, it may serve us well to listen to and actually see the Eastern world).

Only if individualities get to put themselves aside, if they get to empty themselves of themselves in the first place, and offer, in the form of silence, that emptiness to the others, can (and, in fact, does) rise, from and between them, the “communicative sea”, a surge of sounds and meaning.

The words of other people can literally become mine.

Literally, their word turns into mine, we borrow it out of their generosity, so we can lock in it our own concept when we still stutter, when our knowledge of the language still needs to mature with time and practice. Other people’s words which, ultimately, belong to nobody.

They give us our voice when we don’t know or we still aren’t able to pronounce.

They give us the chance to articulate what we had so far only been able to babble; or they convey to us that which is different, the opposite to my idea, although those same sounds I can use, filtering them through myself, to express my own point of view (every concept hides, imminently, the seed of its opposite, especially in the cultures that have cherished the legacy of classical Greek dualistic philosophy; yet, surprisingly, in that same concept we can get a hint of a third choice, the wide middle range).

The same verb used by someone in the question is the one I could use to organize my own statement.

When there is no written text to use as an anchor, to support my oral communication, how not to drown?

Until I can understand myself and my inner worlds as texts to read while I speak, how to avoid the drift of discouragement?

Two possibilities, proven to be helpful by my own experience and by some pupils’, are:

To always allow for a thin thread of true silence after I am done with my part. Inner silence.

To give ourselves the opportunity to borrow from the other person’s discourse the words we may make our own.

Slowly, rhythmically, in that coming and going of acoustic images and meanings, in that giving and receiving to give back again, in what could have been a desert, a co-created ocean emerges, little by little, an ocean whose flow will rise up to the level participants want to and agree they are able to navigate.

What I would most like to point out about this topic is that it is not about philosophy. Nor about some impractical piece of linguistics. It is about seeking an opportunity to give ourselves an opportunity to apply and test for ourselves the efficiency of listening and of silence, from and within our daily experience.

Finally, I quote María Zambrano again:

“Then these words would flow without any obstacles, as if inadvertently. And since, as everything human has to be plural, even in plenitude, there would not be only one word, there would be a multiplicity of words. A swarm of words that will go dwell together in the hive of silence, or in a single nest, not far from man’s silence and within his reach.”

(El hombre y lo divino [Man and the Divine])

Leave a comment